The life of a US Navy Pilot in the Korean War - Milton Solon Kimball

"A Panther Jet unfolds its wings as it fastened to the ship's catapult gear...With helmets, map kits, and oxygen masks, pilots, well briefed for the approaching strike, board their waiting aircraft.

As the catapult officer signals for a full power turn-up, men stand ready in catapult machinery rooms five decks below to pull the lever that will send the jet streaking down the track and into the air at 120 knots.

Above the clouds, a destruction-bombed Panther Jet streaks westward toward the Korean coast. At the head of the formation the flight leaders pinpoint the target on their charts.

The planes move in and are now over the target. The sky is filled with enemy flak which is desperately trying to stop the incoming raiders. Black puffs of death are everywhere.

Then the strike goes in...tons of bombs and rockets plummet earthward. There are brilliant flashes and the whole countryside erupts in explosions of fire and smoke. The guns that had been sending up their deadly fire are now silenced" (Kallaus Jr 1953).

Black puffs of death from the flak of AA guns and spine-tingling drops in their jets for a successful bombing run were daily occurrences for a US Navy pilot in the Korean War. My grandfather, Milton Solon Kimball, was one of those pilots. He was known back home and in the Korean theatre as a hard-working, honest, and disciplined man in every job he had. His Navy career started in Pensacola, Florida to learn the mechanics of an aircraft. Soon after he flew SMJ's in Milton, California, and finished his training in Kingsville, Texas.

Like his father before him in World War I, Mr. Kimball was called upon by his nation to defend the freedom of people that were not his own. Staying in true character, he dived into the opportunity in full confidence that he was going to do whatever it took to keep the Communist North Korean and Chinese troops at bay.

On June 25th, 1950, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) initiated the Korean War through Operation Pokpung. The entire world watched as North Korean soldiers spilled over the 38th parallel and invaded the Republic of Korea (ROK) using Soviet T-34 tanks and Ilyushin Il-10 bomber planes. In only three days, the Communist North Koreans captured Seoul, the capital city of South Korea.

Nicknamed "the bird watcher" by a fellow pilot named Wyatt aboard the USS Princeton. Mr. Kimball was known as having an "interest in what's around plus active" and "keen oversight" (Wyatt 1953).

Flexible and open to choosing multiple variations of the F9F planes, Mr. Kimball's favorite plane to fly was the jet-powered Grumman F9F-5 Panther Fighter, a new F9F variant that carried the powerful Pratt and Whitney J48 Engine. This aircraft was originally used to cover Vought F4U Crosairs during their bombing runs, but as the war progressed, F9F Panthers came to be used as bombers themselves around April 2nd, 1951. This change of tactic was also due to the fact that Panther pilots could not regularly compete with the Soviet's MIG-15s.

The US Navy pilots wanted to avoid MIGs altogether during their time in North Korea for two reasons: First, the out-maneuvering and greater speed abilities of the Soviet MIGs would ultimately make dogfighting extremely dangerous for the American Panthers. According to author Thomas McKelvey Cleaver in his book Holding The Line: The Naval Air Campaign in Korea, "...the F9F-5 Panther was outclassed and outperformed on all points - speed, maneuverability and firepower - by the MIG-15, which was nearly 100mph faster and had a superior thrust-to-weight ratio" (Cleaver 24). The second reason was more political: the intermingling of American and Soviet jets over the Korean Peninsula could spark a larger global conflict between America and the USSR, which could easily tip the entire world into a third World War.

So, in the midst of the Cold War and technological transitions that saw jet-powered airplanes take over propeller planes, Mr. Kimball shares his experience through letters he typed while stationed on the USS Princeton in 1953.

Writing back home on March 14th, 1953, Mr. Kimball gives his review of Korea and his personal thoughts on the difficulty of their mission:

"Korea is a rugged, desolate, and snow-covered country. There is a lack of good targets because they have had so much time to dig in" (Kimball 1953).

Dyett, one of the commanders on the USS Princeton, mentions in a letter that the North Koreans "really know how to make the best of the terrain features" (Dyett 1953).

The Koreans had grown up in these mountain terrains, so it is no surprise that they could hide inside the terrain and maneuver without being seen, but they had to come out at some point to reach their fellow troops on the front lines. When they finally came outside to move equipment and soldiers, the US Navy went to work.

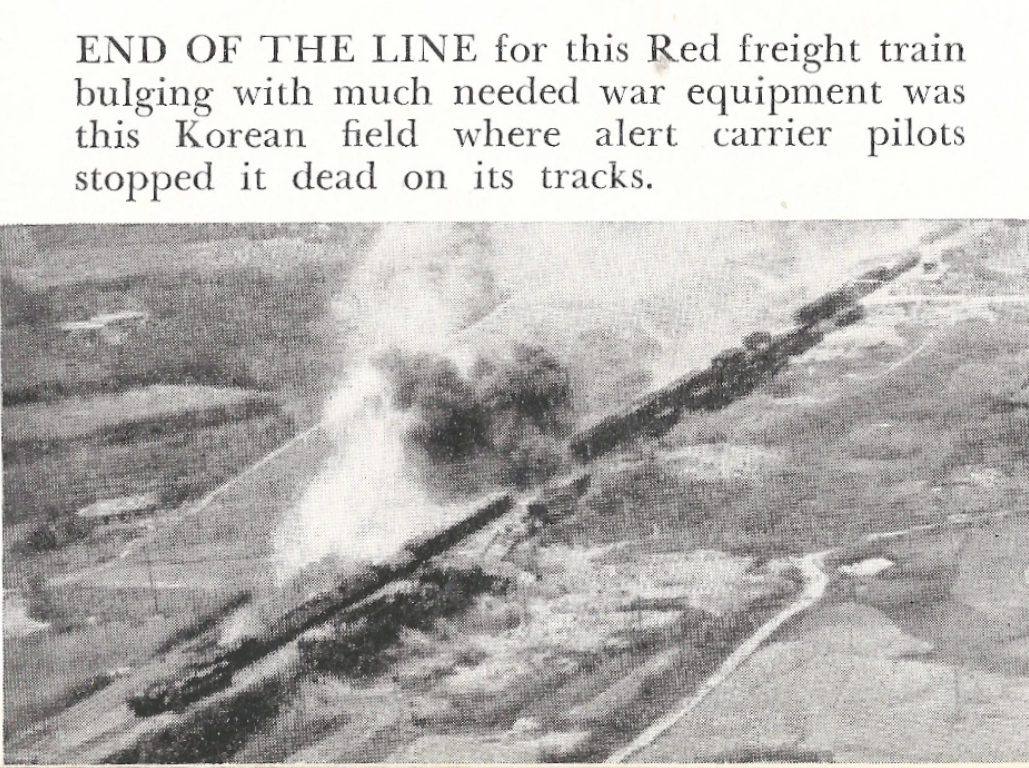

The US Navy's mission in the Korean War can be summarized with one word: interdiction. Every time the US pilots flew into the Korean peninsula they focused on destroying munition supplies, transportation vehicles, bridges, roads, and dug-in Anti-Aircraft guns. The plan was constructed by the United Nations and was known as Operation Strangle.

Unfortunately, the bombardment of ammunition depots and strafing runs of trains and trucks did not impress the United Nations commanders. North Korean troops were still building up on the front lines and this directly affected the United Nation's influence on turning negotiations for peace and the transfer of POWs in their favor. The pilots doing the bombing and strafing runs themselves for the US Navy did not find them impressive as well. According to Thomas McCleavly Cleaver, "...every 'industrial' target in North Korea that could be found had been hit. Pilots complained they were being sent on missions to 'make rubber bounce' (Cleaver 254).

It is not surprising then to find negative comments about the whole operation from Mr. Kimball since their missions seem futile and his friends were being shot down by AA guns. One of those unfortunate pilots was Joe Hall from Task Force 153, a hometown friend of Mr. Kimball and who was known as one "hell of a nice guy" by Dyett. On March 17th, 1953, Mr. Hall was hit by a flak from an AA gun while on a bombing run with Mr. Kimball.

After sharing the news with his family back home, Mr. Kimball adds to his letter:

"Even though this whole operation is a waste, they try to play it pretty safe. Everything is so well dug in and hidden and scattered that the damage we do is not worth the expense."

Knowing the folks back home would be worried about his own safety, Mr. Kimball writes at the end of the letter about the possibility of being shot down himself:

"I don't worry about it - in fact, I'd rather fly over the beach than a CAP, but if they shot back, I'd get out of there fast, and I think the rest will, too" (Kimball 1953). CAP's is the accorynm for Combat Air Patrol.

Similar to other letters written to his loved ones back home, Mr. Kimball gives off the impression that he was not the type of pilot to take unnecessary risks for a mission, but this is not what his fellow pilots witnessed. According to J.J. Clark, Vice Admiral of the United States Navy's 7th Fleet, Milton Solon Kimball's flying personality could be described as "aggressive" in nature:

"Ensign Kimball, while participating in a jet strike on an industrial and military build-up area in the Hamhung-Hungnam complex of Northeast Korea, spotted and reported a target well out from the designated area, furnishing useful information to the flight leader.

Despite intense enemy anti-aircraft fire, he made effective attacks on the target scoring direct hits which resulted in several large secondary explosions.

With disregard for his safety, he repeated his attack on the target accurately strafing the area with his twenty-millimeter cannon fire, thereby providing an aiming point for the remainder of the flight during subsequent runs" (Clark).

In the rest of the letter, J.J. Clark speaks of the success of Princeton's missions and that he authorizes Milton Solon Kimball to receive the "Commendation Ribbon with Combat Distinguishing device" at the end of the war (Clark).

Mr. Kimball's experience brightened up for him in the following month. On April 1st, 1953, he wrote to his family:

"Yesterday I had my biggest satisfaction so far. We hit a supply area and one of my bombs hit a supply building that had explosions in it, and it blew up and started some fires" (Kimball 1953).

In a letter sent to Dick Kimball, Mr. Kimball's brother on April 22nd, 1953, Mr. Kimball explains three different attack coordinations that his squadron has done throughout their time in the air:

"When we go on a flak-suppression hop for a group of ADs and F4Us, there are from eight to sixteen jets, and we try to hit the gun positions around the target, and the target itself, to hold down the AA for the props...

...When we go on a jet strike, we go to a pre-briefed target. We always have photos of the targets, pointing out gun positions, etc. There is always an alternative target, in case of weather or something...

...On the recco hops there are four planes, and primary and secondary recco routes area assigned. There are recco routes all over Korea, usually following the main roads or railroads. On these hops we fly along the route and look for good targets (targets of opportunity)" (Kimball 1953).

When Mr. Kimball and his squadron flew sorties (deployments) across Korea, they were always on a mission. Every plan had multiple fighter jets working together on focused targets or an alternative target if something went wrong with their first objective.

Depending on the division involved in a mission, Mr. Kimball would play the orbital role or the attacking role in the assignment. The orbital role consists of a pilot circling around the attack site, looking for other targets and hoping to distract the Artillery away from his fellow planes doing the main attack. The attacking role has pilots flying low through mountainous terrain to avoid radar and get close enough to have efficient strafing runs and bombing hits.

On a rather unusually calm day, Mr. Kimball wrote a long letter answering some of his brother's questions about his time aboard the USS Princeton on May 6th, 1953:

"I don't know whether I've told you how much we fly. We are kept pretty even within the squadron on the number of hops. I've had 32 hops so far, ten being CAPs. This means one or two hops a day...

Usually in the afternoon when I have time. I go to the work-out room and get some exercise and take a steam bath. That works up a fair appetite. It seems that a standard life aboard ship one eats because of habit, not because he's really hungry. I think what I miss out here are the odors that go with living on land. That must sound crazy" (Kimball 1953).

In the latter days of the month of May, Mr. Kimball's squadron had a short vacation in Hong Kong. But things went back to normal in early June. Rumors of a treaty being signed soon increased the air support and bombing runs of the Navy Pilots. "[...]We're doing everything possible to aid the ground troops - even to the point of flying in seemingly hopeless weather - just on the chance we might find a hole," wrote Wyatt in a June 11th, 1953 Letter.

Mr. Kimball also commented on the pressure of more air support near the frontlines in a letter on June 13th:

"We've been back on the line now for three days. They have stepped up the flight schedule. We've been giving the Commies a lot to look out for. One of the points of the truce (if signed) is that within a few hours after the paper is signed (12, I think), no more war materials can be taken into Korea (north or south). So we are trying to get rid of as much of theirs as possible, and to hit the airstrips and transportation so that they won't be able to bring so much in during the last few hours...I wish they would get on the stick and sign it" (Kimball 1953).

Ironically Mr. Kimball, after dropping hundreds of bombs all over North Korean fields, mountains, and airstrips wrote on June 14th, 1953:

"The Korean Landscape looks much better now - not so desolate. We still don't see much moving in the daytime, and it's hard to believe that they can hold up a front without showing themselves more in the daytime" (Kimball 1953).

In Operation Strangle, the US pilots focused on targets coming into South Korea, but as the war was moving through its second year, the UN soldiers and Admiral J.J. Clark of the seventh fleet wanted the US Navy missions to be behind enemy lines. J.J. Clark's plan consisted of pilots doing what he coined Cherokee Strikes. This type of strike was described as any attack "near the bomb line" in a March 13th, 1953 letter by Wyatt.

Around mid-June, the Navy pilots started to go into the front lines for more Cherokee runs to assist the UN soldiers even if the area was packed with AA guns. Mr. Kimball describes in detail a close-air support mission he was a part of on June 19th:

"We did some close air support (not too close) about 1000 meters ahead of U.N. Troops. We contacted a mosquito (SNJ) and he pointed out the target and marked it with smoke flares. Then we went in and bombed and strafed. The target was enemy gun positions and trenches along a high ridge. There were eight of us and we covered the target pretty well" (Kimball 1953).

In the latter days of June 1953, everyone was flying all day to help push for better negotiations on the table. On June 24th Mr. Kimball writes:

"We had maximum effort for a while, replenishing at night and doing a lot of flying. Most of us had three hops" (Kimball 1953). Hops was a term for flights.

By 1953, Cherokee strikes appeared to have completely altered the chain of command and missions of the U.S. Navy pilots for better and for worse. Since the attacks were in the proximity of the bombing line where the UN troops were, they were given command over the US pilots' bombing and starting runs instead of the USS Princeton commanders. Dyett explained in one of his letters that "a Cherokee strike is near enough to the front lines to require direct control from the ground" (Dyett 1953).

It appears through both Mr. Kimball's letters, Dyett, and Author Thomas Cleaver, that the US Navy pilots did not appreciate these Cherokee Strikes for numerous reasons. In a letter by Dyett on April 17th, he summarizes a Cherokee strike that was done by a couple of divisions and implicates that pilots aboard the USS Princeton were struggling with the ethical dilemma to hit towns that were viewed as military targets. He writes to the men aboard:

"It has been determined that they are almost exclusively for military purposes, and the only civilians present are there for their military usefulness" (Dyett 1953).

When Mr. Kimball was on a Cherokee strike himself on July 17th, he was called off a strike by the UN forces due to fog in the vicinity of their attack area. He and the rest of his mission squadron decided to land at K-18, an US Air Force base in Kangnung. After attempting their new Cherokee strike the next morning, they were called off a second time. On the same day, Mr. Kimball wrote in a letter:

"We get pretty disgusted with the way they handle operations sometimes, but I'll tell you about that in September" (Kimball 1953).

There was pressure from the UN soldiers and USS Princeton commanders to do strikes because the front-line soldiers desperately needed air support as the North Korean and Chinese forces were coming in waves. Some UN troops, according to Dyett, doubted that the US Navy pilots could have successful strikes in the fog near the frontlines. In a few cases, division leaders of Panther squadrons went ahead with their own strikes without UN confirmation due to the confusion of multiple soldiers telling them different commands on the radios. But ultimately, their unsupervised attacks annoyed the UN troops enough to the point that they "would no longer allow flights to try their primaries (targets)" (Dyett 1953).

Just ten days later and after ultimately putting in 200 hours into the F9F-5 Panther, an Armistice Agreement was signed by the United Nations, North Korea, and Chinese military commanders on July 27th, 1953. According to Wyatt:

"The last really offensive mission before the truce was signed was flown by the Tigers...They attacked a large concrete bridge and inflicted severe damage...Milt was disappointed when he got two direct hits that punched two neat little holes in the middle of the bridge, but didn't explode until they were underneath"

After the truce was signed, Mr. Kimball's days consisted of "inspections, reports, paintings, etc" as a 1st Lieutenant. In a letter on August 22nd, 1953 he wrote that he had become bored due to the lack of flying time:

"I sure couldn't take the Navy for a career, because if we aren't flying a lot our collateral duties leave a lot of time with nothing to do, and our pastimes wear out. I'd go out and mow the lawn if they had one around here" (Kimball 1953).

Mr. Kimball not only left his mark through the hundreds of holes left by his bombs and rockets but also through the naming of the Bluetail fly airplane. According to Thomas Cleaver, Ensign Richard Clinite (VF-153) flew a panther that had an unfinished aluminum-colored paint job. The tail end of his plane got hit by flak on May 5th and Mr. Clinite passed away during the incident, resulting in the plane being disposed in a hanger. Ensign W.A. Wilds had his panther in the same hanger due to damage on the forward part of his aircraft. "The maintenance crew took the tail from Wilds' Blue Panther and mated it to Clinite's silver airplane in an all-night hanger deck session. The result was named 'The Bluetail Fly'" (Cleaver 303).

Mr. Kimball had told a story to his family members that while watching the new airplane come up to the deck, he mentioned to a commander next to him that it looked like a blue tail fly. The officer told him that he loved the name and that they would name it the Bluetail Fly.

After the war, Mr. Kimball stayed true to his amazing character by serving the State Bank of Kingsville and becoming their president. In 1974, he received Kingsville's Citizen of the Year Award, and then in 2009, the Otis West Lifetime Achievement Award.

After retirement in 1989, he did tours around the King Ranch as a guide.

Works Cited Page

Cleaver, Thomas McKelvey. "Holding The Line: The Naval Air Campaign in Korea". Osprey Publishing. March 5th, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/Holding-Line-Naval-Campaign-Korea/dp/1472831721

Kallaus Jr, A. Ray. "Attack Carrier U.S.S. Princeton Air Group Fifteen". U.S.S. Princeton. https://www.amazon.com/Attack-Carrier-U-S-S-Princeton-Fifteen/dp/B00AH4U7WU

KCNA. "North Korean Troops in Seoul". AP Images. https://www.rferl.org/a/forgotten-war-the-korean-conflict-70-years-later/30678009.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. "USS Phillipian Sea landing". https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-420000/80-G-420960.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. "USS Princeton scoreboard". Photo #:NH 97075. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-97000/NH-97075.html

Perry, John. US Navy Interdiction Volume: II. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/war-and-conflict/korean-war/navy-interdiction-korea-vol-2/Navy%20Interdiction%20Korea%20Vol%20II.pdf

United States, Navy. "Korea Combat Action Reports for USS Princeton". Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/KoreanCombatActionReportsForUSSPrinceton/page/n17/mode/2up

*Wyatt's letters came with my grandfathers when I received them. He is not shown in the USS Princeton log books but the letters are titled "Wyatt's Digest" and he gives a daily update of what was happening on the USS Princeton from 1952-1953, so I assume he was a commander aboard the ship and that Wyatt was a nickname.

*J.J. Clark's quote about Ensign Kimball also came with the letters, if you would like to see a photo of his quote let me know!

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment